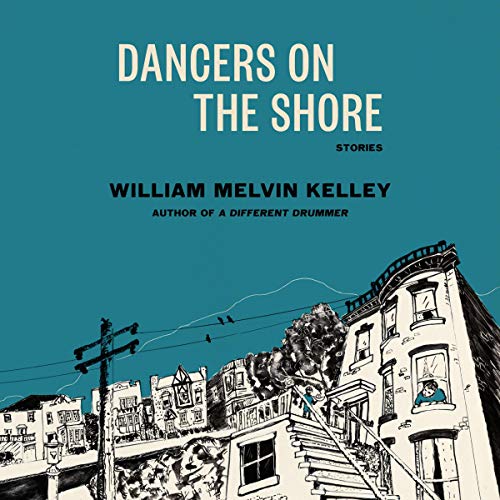

Dancers on the Shore audiobook

Hi, are you looking for Dancers on the Shore audiobook? If yes, you are in the right place! ✅ scroll down to Audio player section bellow, you will find the audio of this book. Right below are top 5 reviews and comments from audiences for this book. Hope you love it!!!.

Review #1

Dancers on the Shore audiobook free

William Melvin Kelley? Who is he? Where has he been? Or is the question “Where have I been.” Short answer: he is a distinguished black author whose career fizzled out after his first novel “A Different Drummer” (1962). “Drummer”, well received by critics and readers, published when Kelley was 24, revealed a significant talent. More good work would surely follow. But not much did. Apart from “Dancers on the Shore” (1965), this collection of short stories, his later work found fewer and fewer readers. Kelley not only believed in his writing, he kept at it throughout his life, working day-in, day out, and at his death in 2017 left two unpublished novels. He taught literature for many years at Sarah Lawrence, made two films about Harlem, issued records of his readings of some of his stories. Cleary he was an author, an artist, a teacher of consequence. But for the great good luck of an intrepid book collector, “New Yorker” writer Kathryn Schulz who happened upon “A beautifully clothbound first edition of Langston Hughes’ novel, “Ask Your Mama” inscribed for Kelley “on your first visit to my house – welcome!”, I still would be in the dark. Schulz’s article about finding the book in an out-of-the-way second hand book shop and the quest it started her on to learn about Kelley inspired me to follow in her tracks. It’s not that easy. Kelley’s books are out of print and are hard to find on the internet. I obtained the copy of “Dancers on the Shore” that provides the basis for this review from a shop in England. The stories will not knock your socks off, but they are all worthwhile. Schulz considers “The Only Man on Liberty Street”, the first of the 16 stories in the collection, and “Not Exactly Lena Horne” to be “the best of them.” “The Poker Game”, mentioned in Hughes’ New York Times obituary on February 8, 2017, a story he wrote as a Harvard undergraduate, is also included., Schulz attributes Kelley’s falloff in favor with readers of his later works to two causes: writing in difficult- to- read dialect better read aloud and to his writing from a white point of view about blacks. Of the latter, Schulz writes “[m]any white readers didn’t want a black writer telling them what they thought . . .”. This trait, while not emphasized in the “Dancers” stories, may be seen in some of them. Endnote. Kathryn Schulz’ piece on Kelley in the January 29, 2018, New Yorker provides a splendid review of Kelley’s literary career. And it does a good job of answering the question “How did he get lost?” FYI, you may be able to find a copy of the 1989 Trade Edition of “A Different Drummer” on Amazon. It has an extensive forward by David Bradley, the author of the “Chaneysville Incident.”

Review #2

Dancers on the Shore audiobook streamming online

Just over three years ago, the New Yorker published a piece by Kathryn Schulz entitled ‘The Lost Giant of American Literature.’ The author, upon discovering an inscribed first edition of Langston Hughes’ poetry in a junk store, set off on a journey to uncover the identity of the recipient. The beneficiary of Hughes’ largesse was William Melvin Kelley. Kelley was a Bronx native who exploded onto the literary scene in 1962 with his widely acclaimed novel A Different Drummer. Over the next eight years, he published a collection of short stories and three additional novels, but then he fell silent. This was not due to death or self-imposed exile in the mold of J.D. Salinger; the public seems to have simply lost interest in his work. When I read the piece, I scurried to find Kelley’s works, but only used copies far too expensive were available. Publishers took note, though, and now Kelley’s works are experiencing a justly earned revival. Late last year, Anchor Books reissued his short-story collection, Dancers on the Shore, and its sixteen stories are some of the best pieces of fiction in mid-twentieth-century American letters. Kelley prefaces his stories with a paragraph from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In the quote, Marlow observes Africans dancing on the shore of the Congo River. Although they may appear primitive and savage to most Europeans, Marlow recognizes a kinship no length of time or cultural winnowing can abolish. Kelley’s choice of Conrad, a man for whom English was a second tongue, is an apt choice. Conrad was a foreigner working in British Empire, and his outsider’s perspective recognized its worst excesses; Kelley, as a black man whose race was still de jure segregated when he wrote these stories, could question the United States with similar sharpness. The ambiguity of one’s position in society is a recurring theme in these stories, especially within the context of families. One of the strongest stories opens the collection, ‘The Only Man on Liberty Street.’ Jennie is the mixed-race daughter of a German immigrant, Maynard Herder, and Josephine, a woman who lives on Liberty Street, the local red-light district in a turn-of-the-century Southern town. Herder is estranged from his wife and comes to live with his common-law family. Each day his legal wife passes by in a carriage, glaring at the home she views as a poor substitute. Although Herder is well liked in the community and respected for his marksmanship, the open living arrangement stirs town gossip. On the day Herder wins first prize at a fair’s shooting contest, Josephine’s own father, a former Confederate general, warns Herder violence is imminent. After a hostile encounter with jeering townspeople, Herder realizes society will break him and those he loves, perhaps fatally, if he fails to return to his wife. He instructs Jennie to go home, promising to return there shortly, and the story ends with Jennie waiting for a father who will never arrive. Another story centered on parental status is ‘The Poker Party.’ This item awarded Kelley his first significant recognition while studying at Harvard. A young, unnamed boy awakens late one evening and watches his parents’ weekly card game. Conducted in the family kitchen, the son climbs into his father’s lap and, through a momentary display of apprehension, ruins his father’s chances in a high-stakes hand. The father irrationally accuses his opponent of cheating, and soon lashes out at his own family in frustration. After being sent back to his room, the boy recognizes the only remaining light within the home emanates from the kitchen, where his father continues to sit alone. One of the most painful experiences of adolescence is the revelation that those adults we love and revere are often deeply flawed. The thwarted ambitions and pressures of life they so desperately try to conceal, when they finally rupture into view, are a frightening and strange epiphany for an innocent mind. A similar breach within the homestead comes about in ‘Not Exactly Lena Horne.’ Two retired railroad workers, Stanton and Wilfred, have jointly purchased a house and settled into relative harmony for twenty years. Wilfred has the eccentric but harmless habit of noting each passing car’s state of origin. His imaginative commentary, combined with a bad day’s case of rheumatism, causes Stanton to finally snap. Threatening to torch the notebooks recording Wilfred’s observations, Stanton shoves down Wilfred when he tries to block their destruction. Although Wilfred is physically unharmed and the notebooks come away unscathed, Stanton’s brief moment of anger permanently damages the friendship. Although individual heartaches provide the most memorable stories, a majority of the stories are interwoven tales about two families, the Dunfords and Bedlows. My favorite story in the collection, ‘A Visit to Grandmother,’ features a seventeen-year-old Chig Dunford accompanying his father on a trip to Tennessee. Chig’s father, Charles, left home decades prior to attend high school and this is his first return. Immediately upon meeting the family matriarch, Chig senses his father’s animus. It is slowly revealed that the source of Charles’ discontent is his mother’s favoritism toward his brother GL. Framed within the story is Charles’ mother recounting the time GL placed her on a horse that ran wild. While she laughs at the incident, Charles knows he would have been belted for similar behavior. When Charles tearfully confronts his mother over her bias, Chig sees a level of emotion never before displayed by his father. Chig’s grandmother is baffled and tries to explain Charles’ and GL’s personalities required different handling, but it is far too late to make amends. In Kelley’s stories, families convey the misunderstandings of one generation unto the next. Chig’s brother Peter is the protagonist of ‘What Shall We Do With a Drunken Sailor?’ An intoxicated member of the merchant marine mistakes Peter for a pimp and attempts to hire him as a procurer. When Peter understandably takes offense, the sailor makes a ham-fisted attempted at friendship. Peter initially plans to send the man on a wild goose chase, but when the sailor reveals his remorse at a failed relationship, Peter displays the grace to leave him where he found him. The last stories focus on Carlyle Bedlow, who would continue to appear in Kelley’s writing up to the late 1990s. To fully appreciate Kelley’s vision, it is necessary to read all of his works. dem incorporates a lightly edited version of a story first appearing in this collection, and Kelley’s last published novel, Dunfords Travels Everywheres, shows the European travels of Chig alluded to in this book. While easy analogies to Salinger’s omnipresent Glass family, William Faulkner’s polyphonic narration, or Richard Wright’s analysis of race all came to mind, his closest predecessor was James Joyce. Each was a man outside his country, but inexorably tied to its cadences. Just as one can see in Joyce interconnected characters and themes throughout A Portrait of the Artist as a Young, Dubliners, Ulysses, and Finnegans Wake, so too in Kelley’s oeuvre. After 1970, no more of Kelley’s books were published. The New Yorker has brought renewed fame to multiple forgotten talents, such as John Williams and Breece D’J Pancake, in recent years, and William Melvin Kelley deserves the same attention. It is regrettable he died in 2017 because the unpublished novels mentioned in interviews now stand a healthy chance of going to press. If so, I look forward to being one of the first in a new generation of readers.